Athletics

The man who wouldn’t give up

Tranent, where I come from, was a coal mining village outside Edinburgh. My grandfathers and most of my uncles were coal miners. Of course, Stawell is an old gold mining town. There’s a nice connection there.

I grew up dreaming of playing football for Hibernian in the Scottish first division and signed for them when I was 16. There were a few of us who were part-time professionals, and we only trained Tuesday and Thursdays. I never really got the chance to develop my ball skills, but the truth is I wasn’t good enough.

Just to pull on the jersey was a thrill, to sit in the same dressing room as men near the end of their careers who’d been heroes when I was a youngster. I left after a few seasons with the nickname ‘Billy Whizz’, given to me by the famous striker Jimmy O’Rourke, after a comic book character who could run really fast.

I only played one first-team game, hitting the bar twice in a 3-0 win over St Johnstone. I’m speaking at the Hibs players’ dinner in April; I’ll be telling them I’ve got a proud 100 per cent winning record. I had no idea at the time what that one game might cost me.

A mate who was a middle-distance runner knew I was quick and convinced me to enter the Powderhall New Year Sprint in 1969. I was still playing football, had only trained for two weeks and got run out in the semis. But I’d caught the bug.

A man named Jim Bradley trained the winner, David Deas. I could see he was in a different class, a proper runner, so I went to Bradley and said, ‘I want to win this next year. Will you train me?’ The only time I’d done athletics was at the school sports.

Bradley said I’d have to build up my upper body. Footballers at that time never paid any attention to gym work, it was all about running and kicking the ball. He had this different philosophy – that the running all came from your arms and shoulders and the harder you could pump them, the bigger stride you’d take.

Then he brought out the speedball. I don’t think he understood the science behind it, but he knew it worked; he had a whole string of winners to prove it. You didn’t lift weights, it was all using your own body weight – pull-ups, press-ups, squats. And hitting the speedball, six three-minute rounds with a minute’s rest in between.

When you were in the gym with him for a three-month period, you never touched the track, never did any running at all. Then when you came on the track, you never did the gym work. It was completely different.

The most I ran was 150 metres – you’d sprint for 60, ease off for 20 in the middle, then pick up speed again for the next 60 or 70. They were very hard sessions, you only had a few minutes’ rest in between. I remember going into the last repetition, being down on the blocks, vomiting as I crouched there, and then he’d fire the gun and you’d be off again.

The training track was the other side of Edinburgh, about 20 kilometres from Tranent. I’d drive home white as a sheet, with that shaky way you get when you’re utterly exhausted. But at the end of the day it worked – my times came down very quickly.

dehydration & DISappointment

One day, Jim traced around my feet on a sheet of paper, sent it off to a man called Hope Sweeney in Melbourne, and a couple of months later a beautiful pair of kangaroo leather running spikes arrived in the post. I called them my ‘Aussies’. I won the 1970 Powderhall Gift wearing them.

Jim had always encouraged his runners, fellas like David Deas and Ricky Dunbar, to go out to Australia and test themselves. Airfares back then weren’t much different to what they are today, something like 400 pounds. I ran off scratch in the 1971 Powderhall and ran well, 11.1 for 110 metres in the middle of winter. When we took off for Melbourne on January 10, it was below zero, and when we landed at Tullamarine it was 40 degrees.

We stayed in a little unit in Nunawading that Ricky Dunbar was living in, all on top of each other. I was training every night in the heat and it was getting to me; we didn’t know anything about fluid replacement back then.

I ended up with constipation and had to have a suppository. I got to Wangaratta at the end of January, a lovely meeting under lights, but I pulled a hamstring at the 80-yard mark.

The last meeting was the Stawell Gift, and when I got there I realised all the other meetings were good, but this was the big one. The organisation was so good, all of those guys in their maroon jackets, and the oval is so picturesque.

The way people spoke about it, not the running public, but the general public all knew about the Stawell Gift. There were big crowds, the place was packed. It just had a special feel to it.

I’d got back into training and ran it, but I wasn’t at my best. I ran 12.3 off scratch and won the Bob McGregor trophy for the outstanding performance for a scratch man. I had it in my mind from then on that this was the one I wanted to win.

I was training in the heat; we didn’t know anything about fluid replacement back then. I ended up with constipation and had to have a suppository.

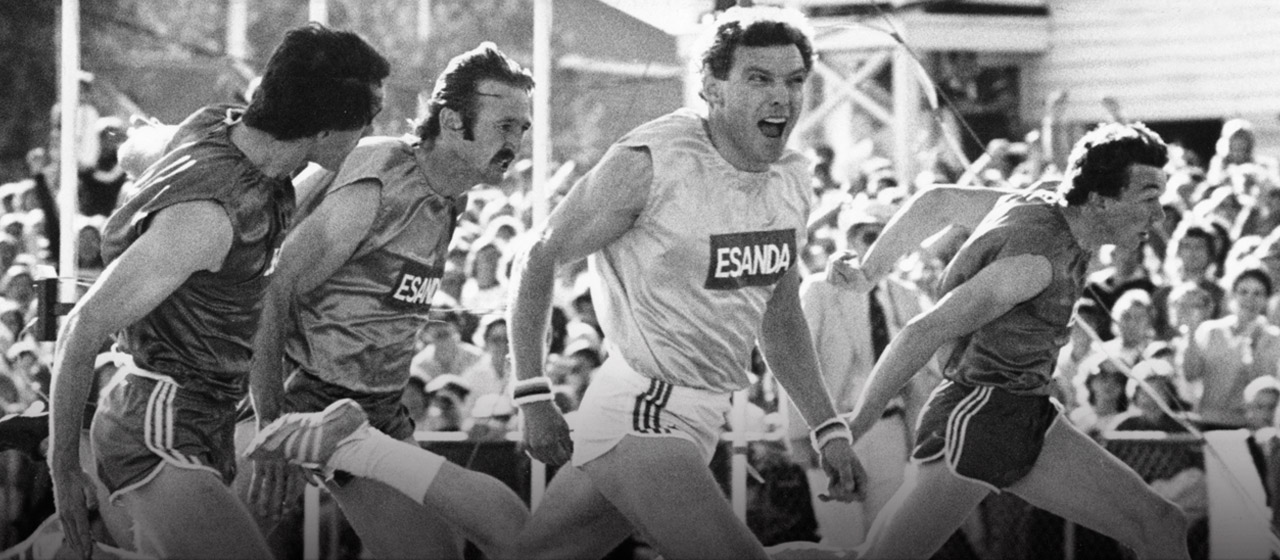

Jim Bradley stayed on and eventually emigrated. He got a job as the fitness man for Essendon Football Club, and later for North Melbourne. He’d never seen a game of Australian Rules. They got a bit of a shock when he cleared the weights out of the changerooms and hung speedballs everywhere.

I came back in 1973, ’74, ’77, ’78, ’79, ’80 and 81, but things went wrong at different times. In ’78, I came with a very small group and we took a new approach. Coming out for two or three months and running lead-up events hadn’t worked, so we thought we’d get fit at home and just come across at the last minute.

We got the cheapest deal we could. We had to fly from Edinburgh to London, London to Moscow on Aeroflot, Moscow to Bangkok. We had 36 hours there, then picked up a Malaysian flight to Kuala Lumpur, then had another 12 hours there. There were only four of us – me, two bookies and my coach Wilson Young – and we landed and drove up to Stawell without any accommodation booked.

We eventually got a caravan. I got run out in the semis, but I’ve made my money back telling that story as an after-dinner speaker.

The next year, Wilson Young decided to bring a bigger group, some younger athletes. He’d caught the bug too. The bookmakers came back with us. I was doing pretty good times, and they weren’t frightened to have a bet. All the guys in the group would give their money to them, and they’d put big bets on.

I was off four metres and got beaten by a few inches by a fella called Noel McMahon. He was off eight metres, another ‘Easter Bunny’ as I called them. But that was the first time I felt I’d shown my proper ability. I was 32 by then, getting on a bit.

I think people were a bit sceptical about my performances over here, and I don’t blame them for that – I wasn’t producing it. But that’s what kept driving me. I’d set a world record for 120 yards that still stands today, had beaten Mexico 200 metres Olympic gold medallist Tommie Smith, of the ‘Black Power’ salute, in a four-race match series in 1972 to be crowned world professional sprint champion.

But I think people doubted me, and that drove me on. It was nothing to do with money. If you made a profit and loss account of my attempts to win Stawell, I’d be on the debit side.

In 1980, they put me back to scratch and I made the final again. John Dinan won, another good runner off a good handicap. Then in ’81, everything just went right.

the party was massive

1981 felt different, I didn’t have any injury problems or niggles. I was out there a few weeks before and there was a chap called Lal McAllister, an osteopath, who took a liking to me and wanted me to win it. He obviously had a Scottish background going way back. I went out to his place in Strathmore two or three times a week. He kept my body in shape.

Maybe because I’d experienced it for so many years and been in the previous two finals, Stawell no longer daunted me. The pressure lifted off me and I was quite confident. The bookies came out with us again and had a real go but the betting never really concerned me, I never bothered my head if they lost money on me.

My best pal Bert Logan, who I went to school with from our first day, was with me too. We went for a walk on the Sunday night, and all the wee stores on the Stawell high street were displaying the different prizes for all of the races on Easter Monday. The Gift medal was there, and I said to Bert, ‘If I win that tomorrow I’ll give it to you’.

I think every sportsman knows the feeling, when they’re really at the top… the modern ones talk about being in the zone. There were times when it felt like you were floating, almost slow motion, and there was a bit of that for sure that day. It was magical.

And no, I don’t even have the medal. Bert’s a bookie too – we won $40,000 on the punt, so he got the medal and the money.

Singing Flower Of Scotland on the victory dais was kind of planned, although I was never sure I’d get the chance to do it. I had it in my mind that I’d do something like that if I ever won. I don’t consider myself a singer, but I’m very game. I think it’s all connected to your personality – you’re not afraid to put yourself on the line, whether it’s to get up and deliver a speech or sing a song, run a race. These are all things that terrify a lot of people. But I’ve always liked the challenge.

I think that’s why the Australian public eventually took to me. As a nation you’re battlers, and they’d seen how much it meant to me to win this race. When I eventually did win it, nobody begrudged it.

We were staying at Ken and Patty Robson’s, who had a beautiful house about 100 metres from the Central Park front gate. Ken was a stonemason and a committee member at Stawell. The party back there was massive, we went through crates of champagne.

I’ve no regrets at all about that one game for Hibs ending my amateur status and disqualifying me from competing for Great Britain at an Olympic or Commonwealth Games. I was put into professional running, and I enjoyed it thoroughly. I never look back with any bitterness. Even the tough times, you look back now and they were quite funny.

I’ve made a life out of telling my story, as an after-dinner speaker and more recently in a one-man stage show I started in 2014. I did McNeill Of Tranent down in the Borders a few months ago; it’s telling stories, adding a bit of film and pictures as I go along. I even rig a speedball up on the stage and give a demonstration. The show tells people over here about Stawell, they see the crowds and get an appreciation of how big it is.

I’ve got one more ambition: I’d love to do it at Stawell, in the wee town hall where they used to do the betting for the Gift. It’s a lovely community place. That would be wonderful.

More about: Essendon

Load More

Load More