Basketball

Cape York to the NBA & back

I spoke Torres Strait Creole, Brokan, growing up in the small community of Bamaga, about 40km from the tip of Cape York.

Our house was a two-storey place on Sweet Corner. I couldn’t speak my dad’s language, another from the Torres Strait Islands, but I could understand it – especially when I was in trouble. Although I didn’t really find serious trouble. Mum and dad made sure of it. With plenty of trouble to be found in Bamaga, mostly caused by alcohol and drugs, I had a strict curfew.

My parents, Ron and Lynette, demanded that I be inside and showered by 5pm every night. If I was even one minute late, I was in trouble.

Dad was the local police sergeant. And of the 1000 or so people living in Bamaga, I’m related to 200. It is a huge family. There was always someone keeping an eye on me and if one of my older brothers snuck out of the house, or one of my cousins, people would always report it back to dad.

Trouble wasn’t a temptation, because it was never an option with my mum and dad.

The main challenge in Bamaga is boredom. That’s how kids, and adults, fall into the trap of substance abuse.

Bamaga is close to the sea, about 20km. We have rainforest and bush, creeks and rivers. There’s a lot to do, if you look. Mum and dad always kept us busy on weekends. We’d get out of town to go fishing and diving.

We saw the beautiful side of our home. Mum and dad protected us from the other side; the drinking, the partying, the cycle of damage.

In town, there’s a pub and not much else, so going there and getting drunk is the default option. Then you get kids sneaking out of home, taking alcohol off of older people, and the problem begins early in the younger generation.

Mum and dad were also big on education. That, combined with their desire to shield me from Bamaga’s problems, meant they sent me and my brothers away to Cairns for school.

I did Year 7 at Tablelands, then Year 8 and Year 9 at St Augustine’s. It was tough being away from home at that age.

I was very shy, I think mostly because English was my second language and I wasn’t very good at speaking it. I had to break that barrier before I could start to relate to people.

There were positives, too. It boosted my education and it eventually gave me some comfort with being away from home, which helped later on with basketball.

But I grew homesick. I returned to Bamaga.

The problems grew worse as I got older. By now, I could see them clearly. There were young girls, some my schoolmates, getting pregnant. Old friends were underage drinking, heavily.

Mum and dad deserve so much credit for the way they raised us; me, my brothers Mark and Chris, and my sister Moana. All the strictness paid off.

Their lessons, and what I saw become of other people in Bamaga, left me with a deep desire to help my hometown.

More on that later.

UNCLE DANNY & BASKETBALL

I stand at 6’10” (209cm) these days. I had a huge growth spurt at 16.

I was around rugby league my whole life growing up. It’s the most popular sport in Bamaga. I loved to play – but after that growth spurt, I was too big. I stopped playing.

That’s when Uncle Danny came to town.

Danny Morseu was kind of intimidating to me as a kid. I knew what he’d done, which was extraordinary.

After growing up on Thursday Island without running water or electricity, Uncle Danny was the first Torres Strait Islander to represent Australia at the Olympics, playing with the Boomers at Moscow 1980 and Los Angeles 1984. He also won three NBL championships, with the St Kilda Saints (2) and Brisbane Bullets, and won a QBL championship coaching the Toowoomba Mountaineers.

He was the first Indigenous player inducted into the NBL Hall Of Fame, and later worked in Indigenous health.

I was very shy, I think mostly because English was my second language and I wasn’t very good at speaking it. I had to break that barrier before I could start to relate to people.

Uncle Danny came up to Bamaga for a basketball camp when I was nearly 17 and asked me, ‘What are you doing?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Why don’t you try the game of basketball?’

I wasn’t a fan of basketball growing up, but Uncle Danny encouraged me. He saw talent in me. I was playing in a three-on-three competition when he asked if I wanted to have a proper crack by coming down to play in Cairns with his Indigenous team, Kuiyam Pride. I said I’d try it for a year.

But when Uncle Danny moved to Canberra and I ended up at the Cairns Marlins, the QBL team, I was asking what I’d gotten myself into. I didn’t like it, to be honest.

I was scared. Intimidated. There were guys like Kerry Williams and Aron Baynes playing. I used to stand at the door of the gym looking in, I didn’t even want to come on the court.

Then one week, the boys came and grabbed me and I started practising with them. I opened up a bit and it was all good. I finally fell in love with the sport.

BAMAGA TO CANADA

I played in an ABA national final for Cairns Marlins, against North West Tasmania, when I was still just 17. Mark Beecroft was the head coach.

I had an impact off the bench, we won, and I got the opportunity to spend two years at the Australian Institute of Sport. Even though I was shy, I got on with the guys; like Patty Mills, who was there at the same time. He was from Canberra and it was nice to spend time with his parents, Uncle Ben and Aunty Yvonne, when we got homesick living in the dorm.

I liked the AIS, but it wasn’t always a perfect fit.

It was freezing cold, of course, and I’d get into it with the head coach, Marty Clarke. There were times I wanted to quit. But thankfully, I had a lot of support around me.

The opportunity to go to college in the US, at Midland College, came out of the AIS. I really didn’t want to go. Marty pushed me towards it. My academics weren’t good there and after just three months, I hurt my knee; a meniscus tear that needed surgery.

I came home around Christmas, and had to see a specialist in Melbourne. I needed to rehab it properly, so I stayed at home and did that, then focused on playing with the Cairns Marlins again.

The NBA came calling. I was drafted with pick 41 by the Indiana Pacers and traded to the Toronto Raptors. I couldn’t believe it. From Bamaga, to Canada.

The next NBL season, I became a rookie with the Cairns Taipans.

I was a nobody, coming in. I didn’t have an offensive game. I was raw. I was lacking confidence.

But with the Taipans mentoring me, things clicked fast. Being a part of the organisation gave me confidence, and it helped me see the abilities that I had. That first year in the league was fun.

I had incredible teammates too, like Martin Cattalini, Darnell Mee, Rashad Tucker and Larry Abney. They guided me through my first professional season and I won Rookie of the Year in 2008.

Then the NBA came calling.

I was drafted with pick 41 by the Indiana Pacers and traded to the Toronto Raptors.

I couldn’t believe it. From Bamaga, to Canada.

But right from my routine physical in Toronto, I was behind the eight-ball.

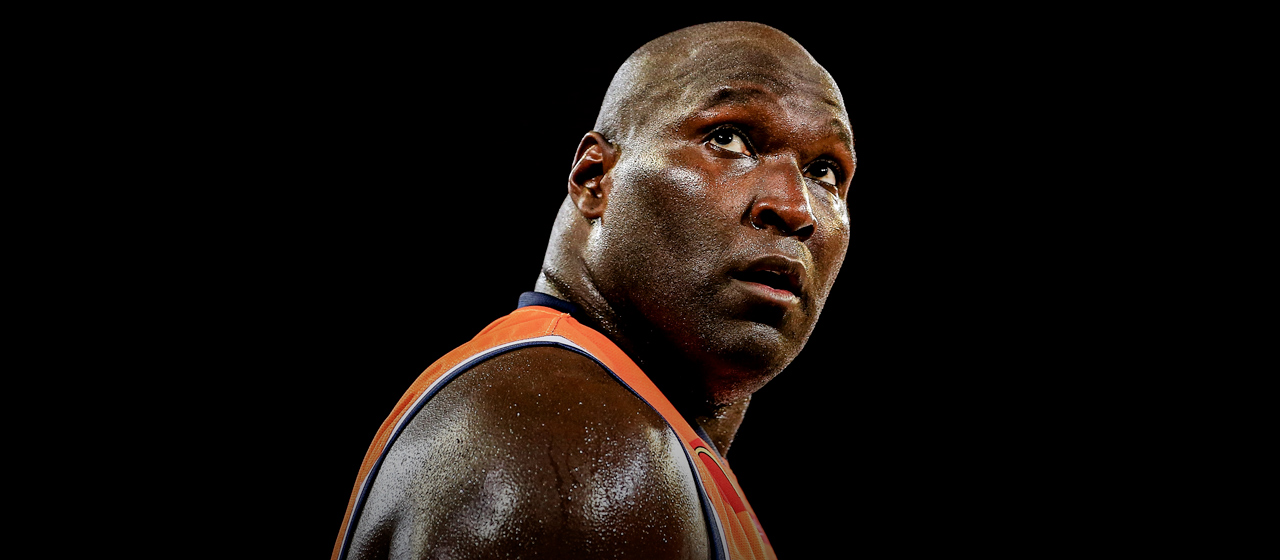

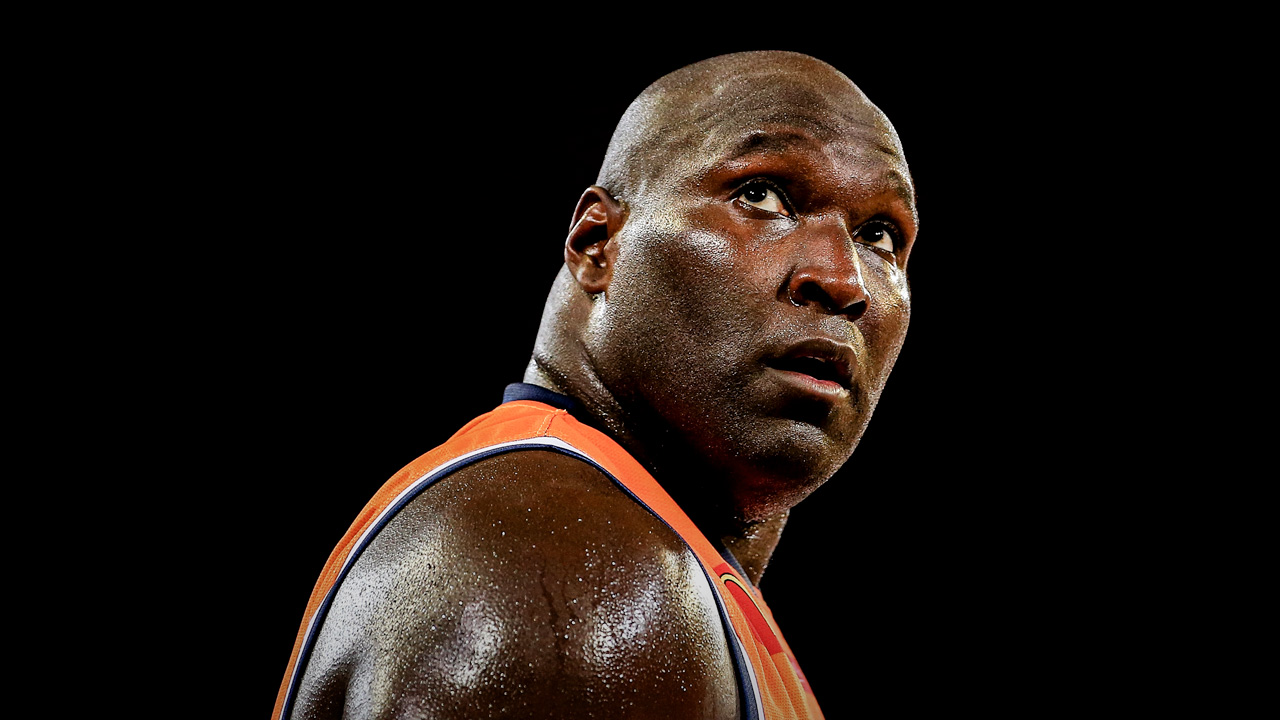

NBA HIGHS & LOWS

The heart scare was a shock.

It was a diagnosed irregularity that I couldn’t feel, I didn’t know what was going on. I’d never had any issues and suddenly, I’m worried that I have heart disease. I couldn’t even work out.

It was a big setback right when I was starting out in the NBA, although eventually I found out it wasn’t as serious as first thought.

We were trying to make the playoffs when they told me that I was going to be playing.

I was nervous, because I didn’t have any games under my belt and we didn’t practise much during the season. I wasn’t really prepared.

But I was also very happy. The night before, I couldn’t sleep. I’d been through all the medical check-ups and I was good to go. The excitement was overwhelming. It was a proud moment.

I became the first Indigenous Australian to play in the NBA.

More about: Andrew Bogut | Aron Baynes | Boomers | Cairns Taipans | College basketball | NBA | NBL | Patty Mills | Perth Wildcats

Load More

Load More