NRL

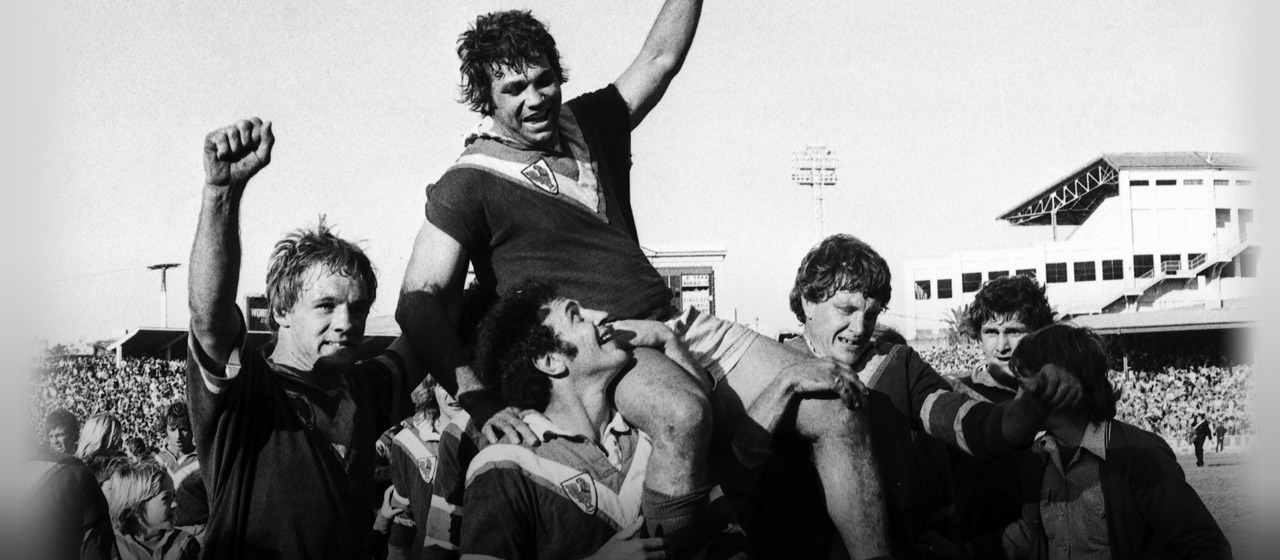

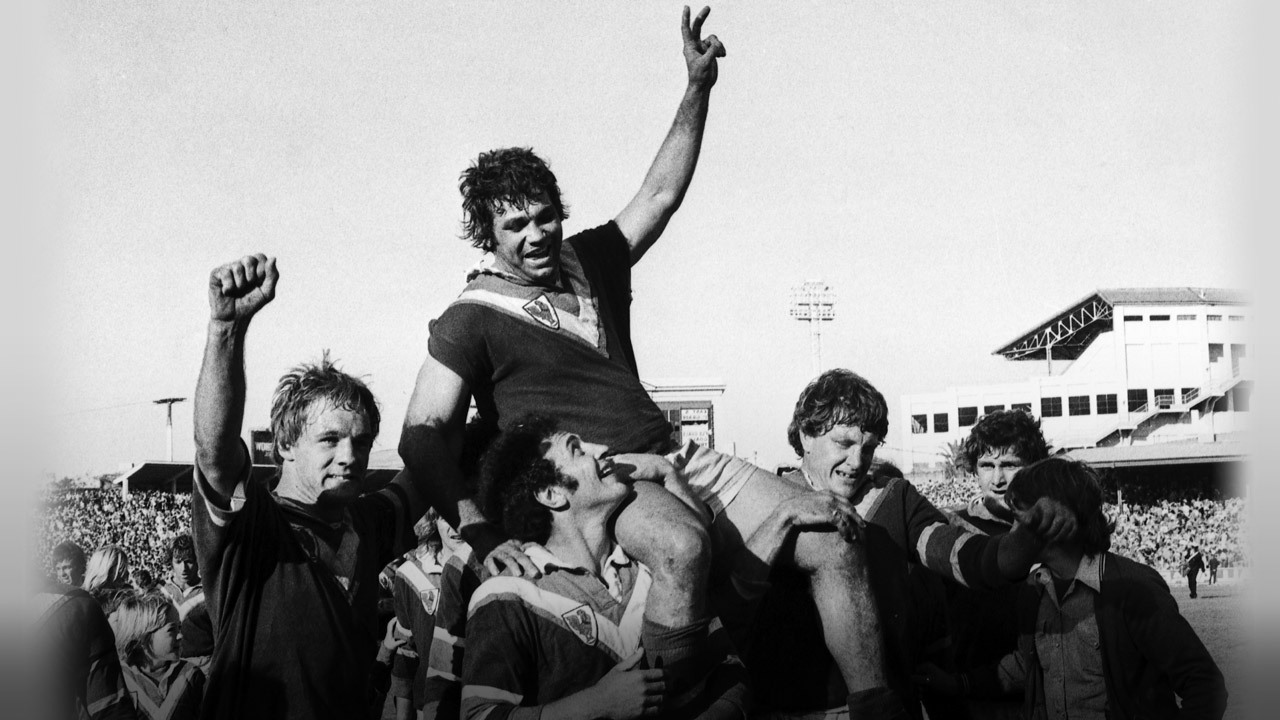

The man who changed a nation

Indigenous people weren’t counted among the Australian population until 1967.

Six years later, one of our own was captaining the national rugby league team.

That man was my dad, Arthur Beetson, and I think it’s important we keep telling his story so it is not lost through the generations.

In America, the breaking of the ‘colour barrier’ in sport is celebrated every year. We’re not quite as big on our history here. But when you stop and think about the significance of an Indigenous man being named Australian captain in 1973, it has to be up there with the most significant sporting and social achievements in our country’s history.

Dad showed his generation what was possible. And he opened the door for future generations to follow in his footsteps.

There’s no doubt in my mind that many of the opportunities available to Indigenous players today started with the groundwork laid down by Artie over the course of his life. The fact there is an Indigenous Round this week shows how far we’ve come as a game and a community. He couldn’t have dreamed of anything like that back in his day.

I like to think that Dad rose above footy in the end.

That’s not intended to talk the game down in any way – the big fella loved footy – but, over time, it became the vehicle for him to speak to Indigenous people about important issues like education and health and employment.

He changed so many lives. He continues to do so.

Of course, dad wasn’t the only Indigenous pioneer in rugby league. There were many before him and many after. But his contributions were important and I’d like to share some of them with you.

Arthur Beetson – Kangaroo #408'Big Artie' was the first Indigenous person to captain Australia in any sport….

Posted by Australian Kangaroos on Saturday, 2 July 2016

A GUBI GUBI MAN

Dad came from the Gubi Gubi people on the Sunshine Coast. That was on his mother’s side.

Her name was Marie Loader and she was a member of the Stolen Generation. They took her from Buderim and moved to her to Cherbourg when she was young. I lived with her for a few years when I was little. I don’t remember all her stories, but I know enough to say that life was tough for her.

Artie’s father, Bill, was a hard man and Artie took after him. He didn’t ask for favours from anyone. He knew talent was nothing without dedication. And he was stubborn. He had to be to get to where he did from where he came from. There were parts of Roma, his hometown, that Indigenous people weren’t permitted to enter.

Dad was big on education. He was the first member of our family to finish school at Roma State School. He was doing his apprenticeship as a postie when he got signed by Redcliffe.

They nicknamed him ‘Bones’ in the beginning. He was only a skinny fella and he played five-eighth. He put on a stone at Redcliffe and another two when he signed with Balmain. If you’ve seen photos of him, you’d know that he added quite a few more over the years, the big fella!

He endured a lot of racial discrimination on the footy field. That’s just what happened in that era. There’s no value in repeating the things that were said to him other than to say that if a player acted like that today towards an Indigenous opponent, they’d be charged and banned for a long, long time. It would happen to him all the time.

Dad didn’t say much about it. To be dark-skinned meant you had to be thick-skinned back then. You had to have a ‘water off a duck’s back’ attitude. He didn’t complain to the media or the authorities, who probably wouldn’t have done much about it even if he did.

He just made note of who said what to him and dished out his own form of justice on the field!

There were parts of Roma, his hometown, that Indigenous people weren’t permitted to enter.

All the Indigenous footballers in that era put up with racism and they shared a bond that probably not a lot of others understood. Dad had huge respect for Vern and Frank Daisy. They were legends up north, a couple of good-looking fellas who used to get around town in their cowboy hats. They played in the Foley Shield until they were 46 or 47. They won something like seven titles for Mount Isa during their careers.

Vern and Frank were in the first all-Indigenous rugby league side in 1973, which toured New Zealand. Wally Tallis, Gorden’s father, was part of that squad, too.

What those men did was real, pioneering stuff. They achieved things no one had before them.

The same went for Dad. When he captained Australia, no Indigenous person before him had led a major national sporting side. It was something he was proud of. It opened up a whole new world of possibilities for Indigenous people.

Dad also realised as his career went on that rugby league gave him a platform to speak about important issues for his people. He wasn’t just a footballer, he was a role model.

Australia had its racist elements in those days but sport, more than anything else, had an ability to bring people together. When Dad realised that, he really started changing people’s lives.

BIG MAN, BIG HEART

Artie helped the Indigenous community in so many ways.

He brought young guys like David Peachey, Dean Widders, Nathan Blacklock and Justin Hodges into our house in Matraville and looked after them. Dad understood it could be a daunting thing for young Indigenous kids to move to the big smoke. He wanted to do his bit.

He’d talk to anyone. Whether he was playing, coaching or scouting, Dad had a way about him where people felt comfortable to pull up a chair and have a chat. He met people all over the country. A lot of that was because he drove everywhere – he was a big unit who didn’t like to fly – so he would find himself in big cities and country towns all the time. He’d take the opportunity to talk to the Indigenous community about education, closing the gap and the issues that were important to him.

The government appointed him an ambassador to Indigenous people and from that he launched his foundation, which I’m a director of today. My brothers Kristian, Mark and Scott are also involved. Their partners and kids all pitch in too. It’s a real family affair.

Among other things, we run the Murri Carnival. It’s the biggest Indigenous rugby league carnival in Queensland. In addition to playing, everyone who attends has to undergo a health check, which we organise. It’s blood pressure, heart, diabetes and all that sort of stuff.

We do 3,000 health checks per carnival and we’ve conducted seven carnivals, so that’s 21,000 health checks. There have been instances where people have been taken to hospital straight away because they’ve been detected with heart problems, acute diabetes or something along those lines.

These are kids from Torres Strait, Badu Island, Normanton. We had a team come down from Weipa last time. Many of them wouldn’t have access to health checks like this. They come for the footy, but they take a lot more than a trophy away with them.

We’ve got a tournament coming up next week, the Arthur Beetson Outback Challenge. There’ll be kids coming from Normanton all the way to Gundawindi. There are boys and girls junior teams. It’s in partnership with Queensland Police.

He wasn’t just a footballer, he was a role model.

Dad touched the lives of people all over the world. When he passed away in 2011, we had people from England, Western Australia, South Australia and all over fly in for his funeral.

I remember getting in a taxi in Tasmania once. The driver saw the name on my credit card and asked, ‘Are you any relation to Big Artie?’ I was like, ‘How do you know about him down here in Tassie?!’

He did a lot for Maori people as well, which isn’t so well known about. He would head over to New Zealand in the 1990s to help coach Maori sides. We’re still dealing with people who Dad connected with over there.

Dad started all this and we’re continuing it today.

That’s my life.

INDIGENOUS ROUND

Dad would’ve loved Indigenous Round. Our people punch well above our weight in rugby league. We only account for two per cent of the population but there have been periods where almost 40 per cent of the national team have been Indigenous players.

The Roosters jersey will have Dad’s face on the front of it. My cousin, Bianca, helped with the design. She’s a famous artist. It means a lot to our family.

The Sydney Roosters will continue to celebrate Indigenous culture and also honour a Roosters legend with the unveiling of their 2018 Indigenous jersey https://t.co/PtRNxZfDAT pic.twitter.com/qcKw9FENsE

— Sydney Roosters (@sydneyroosters) May 1, 2018

Bianca and Dad also spent a bit of time putting together our family tree in the last few years of his life. The older Dad got, the more his Indigenous roots meant to him. A couple of years before he passed away, he drove through parts of NSW to learn more about his dad’s side of the family.

By the time he passed away, he lived a full life.

There were lots of accolades for his footy, but he wasn’t big on that. The things that meant to him most were the lives he was able to positively impact through the game of rugby league.

That’s what I’ll be thinking about this Indigenous Round.

More about: Indigenous Australians | Kangaroos | Racism | Sydney Roosters

Load More

Load More